Our thanks to Dean Herrick for his help with this post.

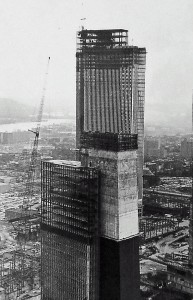

Of the more than 90 prime contractors and hundreds of subcontractors at the South Mall site, only one was ever fired by the State of New York: The Foster-Lipkins Corporation, builder of the Corning Tower and the Swan Street Motor Vehicle Building. The contractor’s performance on the 44-story tower was, at times, dangerous and embarrassing. And it was ultimately costly to the State. Yet firing Foster-Lipkins was not an easy choice for the South Mall construction coordinators.

State officials knew that bringing on a replacement contractor would increase both costs and delays. They also knew that, of all the South Mall contractors, Elliott Foster and Milton Lipkins were particularly skilled in the art of brinksmanship. Foster and Lipkins finally exhausted the State’s patience in the spring of 1970, when their firm demanded an additional $21 million—double the amount of the initial contract—to finish the tower.

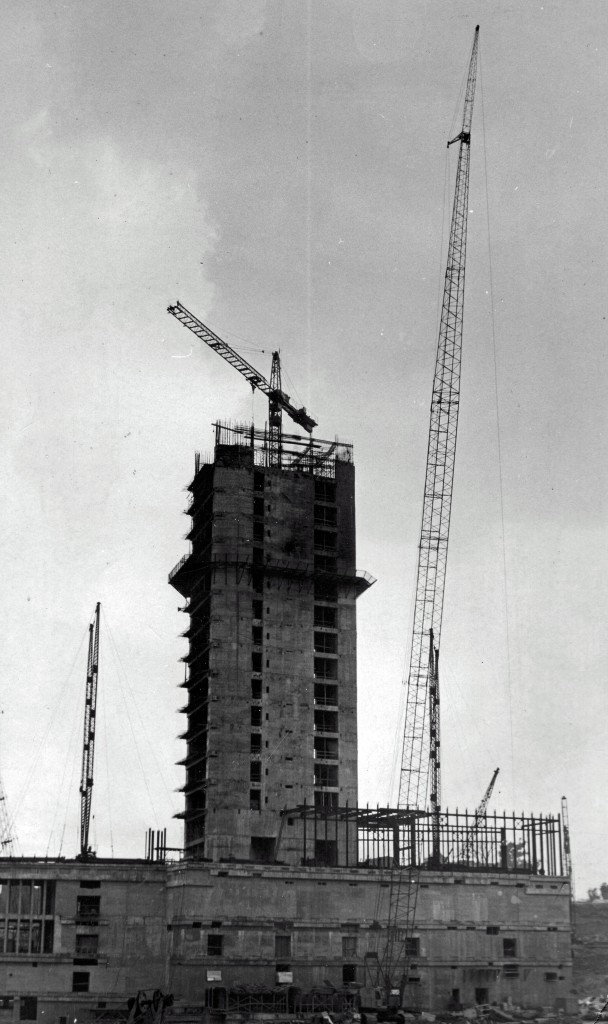

Foster-Lipkins began work on the site in April 1966, and the complaints and excuses began piling up almost immediately. The conflict between the State and the contractor became increasingly intense over the next four years, neither willing to give in in order to preserve the working relationship. Ultimately, Foster-Lipkins was fired.

What was at stake in this protracted dispute, and who was at fault? From documents at the New York State Archives, we know the State’s position. But we thought a discussion with a Foster-Lipkins foreman might provide a different perspective.

Carpenter Dean Herrick began work on the tower in 1967. In 1972, he fitted the final touches. Dean was involved in nearly every aspect of construction. He worked 35 hours per week of “straight time,” but there was always overtime. And as he remarked, as a foreman, “you made your own deals.”

Dean was aware that the office tower was unique, because it was, in a sense, two buildings: a reinforced concrete core with a steel frame around it and a concrete encasement for fireproofing. The structure, designed by architect Wallace Harrison, was ahead of its time. Dean remembers escorting international visitors, who marveled about the advantage of the concrete core, which served to stiffen and stabilize the structure against the lateral force of wind.

But there were distinct disadvantages to the design, a point on which Dean agrees with his former employer: while the height and width of the rising core remained the same, the steel frame, particularly on the sunny southeast corner of the building, expanded. It was, therefore, an ongoing and frustrating challenge to make doors, window caulking, and everything else line up. This central design character—or flaw, depending on one’s perspective—was at the heart of the site’s mounting problems.

But the tower’s design was not the main, or only, problem faced by Foster-Lipkins. To begin, work that was to commence in April 1966 did not get underway until many months later. According to Foster-Lipkins, their workmen initially could not access the site. Three months in, the company complained of “delays, hardship, damages, and deterioration of relations between our office” and the George A. Fuller Company, the company hired by the State to manage South Mall construction. To Foster-Lipkins, the Fuller company was “their competitor,” assigned to supervise their work. As delays mounted to the point that the project was more than a year delayed, the steady and irritable stream correspondence between Fuller and Foster-Lipkins became even more bitter. Not only did the company fault the State for the performance of its architects, engineers, and the proximate contractors who interfered with its work, but Foster-Lipkins also blamed their own subcontractors. In particular, the contractor faulted Bethlehem Steel, its largest subcontractor, for faulty steel erection, short of the specification requirements set by the American Institute of Steel Construction. When Foster Lipkins refused to pay Bethlehem, the subcontractor successfully sued to recover the $1.5 million owed.

Indeed, many “extraordinary interferences” caused numerous delays, which put work out of sequence. With each setback, the price of labor and materials ratcheted upwards. In July

1967, a fire so damaged the tower and the crane atop it that firefighters were ordered out for their safety.

The fire set construction back several weeks, and in subsequent litigation, both the State and the contractor heaped blame upon the other. At least half-a-dozen smaller fires erupted in elevator shafts, debris chutes, and around salamander heaters. A spokesman for the Office of General Services blamed “poor housekeeping.” And yet there is another side to this story. Dean pointed out that the tarpaulin and plastic used to swaddle the edges of the building in winter would loosen and whip around in high winds. This material was fuel for the salamanders.

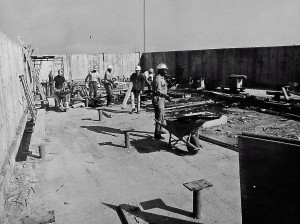

And yet, there is damning evidence of negligence by Foster-Lipkins. Just after quitting time on November 3, 1969, a 22-year old laborer fell 22 stories down a buck hoist shaft to his death. Six weeks prior, the South Mall Safety Director had inspected the site and ordered the contractor to rectify 19 “unsafe conditions,” including installing protective barriers at all floors on the open end of the hoisting landings. Inspection of the tower building after the fatality revealed that “no protective recommended barriers were provided.” Dean agrees that rails or gates would have improved safety on the project. The evening after the fatal accident, he recalls staying late to talk with investigators, while electricians connected a new intercom system to operate the buck hoist.

Although the South Mall site teemed with workers, it seemed that there were never enough men working on the tower. Foster-Lipkins blamed its subcontractors. The State pointed the finger at Foster-Lipkins. In a January 1970 letter to Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, the OGS Commissioner complained that the tower work “was not moving” and had “come practically to a standstill.” It turned out that Foster-Lipkins had been slow to pay its subcontractors, who, in turn, were unable to hire a full workforce. That spring, Milton Lipkins admitted that the company could no longer pay its subcontractors. The State Comptroller’s office attempted to devise a new means of financing the construction, amidst reports that Albany banks had been slow to cash checks issued by Foster-Lipkins. Despite this, Dean tells us that the New York-based project bosses regularly “borrowed” carpenters and laborers to assist with personal auto repair and home improvement projects.

Foster-Lipkins telegrammed its complaints to its subcontractors and to the State, sometimes as often as once or twice a day. The contractor’s extraordinary catalogue of blame included: a wildcat Teamster’s strike caused by Bethlehem Steel; an improper concrete mix “that the State had approved”; the slow approval of shop drawings by project engineers; and the many changes in design demanded by the architect. The company maintained that it never received proper direction from the State. Stanley Lipkins averred, “The only thing we’re saying and pleading for … is for God’s sake tell us what to do.” He complained, for example, that engineers’ changes to steel specifications “threw everything off.” As a result, windows and caulking, flashing and finishes would have to be reworked.

State officials saw evidence of a troubling pattern by Foster-Lipkins and looked askance at the company’s demand to renegotiate its contract, even as it continually “refus[ed] to accept directives.” The final straw was when the contractor stated, categorically, that “only” if “additional significant funds were provided would the project move more rapidly.” State officials sought a compromise. But Foster-Lipkins balked. And a new contractor, Dic Concrete, was appointed by the project’s sureties.

The new contractor completed construction of the tower in 1972. Three years later in 1975, an OGS attorney recommended a $9.5 million settlement for Foster-Lipkins. “That comes to about half a buck for every man, woman and children residing in New York State,” reporter Richard Karp pointed out. The same OGS attorney was later convicted for accepting $22,000 in bribes from a Foster-Lipkins subcontractor.

Although much of the dispute between the State and Foster-Lipkins was above his pay grade, Dean was not particularly surprised to learn of it. But for him, building what we now know as the Mayor Erastus Corning II Tower was exciting, interesting, and well-paid work. “I was fortunate, very fortunate,” he told us.

Note: The publicity photo at top (or to the left) of this post shows Dean Herrick standing on the 35th floor of the Corning Tower, ca. 1969.

Ugly building that should never have been built. It’s a blight and the Egg adds to the Ugly of downtown Albany.

Rockefeller wasted enormous amounts of taxpayer money on his tacky taste and “modern” art and architecture.

It’s now 2021 and Albany has yet to crawl an inch back to its once vibrant landscape of pre-Rockefeller.

But gee! Rocky did die with a smile on his face via a Happy Ending. Sadly, wife Happy was Not happy about the real cause of his heart attack.

LikeLike