Our thanks to Scott Christianson for his help with this post.

Fresh out of college and newly married, Scott Christianson—an aspiring investigative reporter and former hometown football star (Bethlehem Central)—took a job at the Knickerbocker News in the summer of 1969. Over the course of several months, he moved up the journalistic ladder from copy editor to assistant editorial page editor, reviewer, general assignment reporter. That summer and fall, Scott helped edit coverage of the moon landing and launch the Knick’s Weekend Magazine. But his story assignments were not especially inspiring—in mid-December, a review of the movie, “Once You Kill a Stranger” (a remake of “Strangers on a Train”), followed by a piece on books as Christmas presents.

Scott hungered for meatier challenges. During his senior year at the University of Connecticut, he had written for the Hartford Courant and served as editor of The Thirties Times, a weekly insert in the Connecticut Daily Campus that reprinted Depression-era news stories. The Times was part of an innovative, campus-wide, interdisciplinary curriculum focusing on the “The Thirties Experience.” This educational experiment taught Scott to admire—and, eventually, to emulate—an earlier generation of writers, who exposed corruption in order to spark outrage and spur reform.

Scott’s chance to rake muck arrived with a blizzard that shut down Albany for most of a week. On the worst day of the December 1969 storm, Scott was the only reporter—and one of few Capital Newspapers employees—to show up for work, after skitching a ride on cardboard down Delaware Avenue from Delmar and making his way on foot to the snow-bound Sheridan Avenue plant. Publisher Robert Danzig took notice. “My career took off after that,” Scott tells us.

Albany’s notoriously treacherous streets and sidewalks had attracted scathing notice from New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg earlier in the year. Schanberg described Mayor Erastus Corning’s administration as “resolutely backward,” treating “icy patches and grimy snow clumps … almost as sacred monuments.” Scott found that snow clearance for the winter of 1969-1970 cost taxpayers over $2.1 million but left “a significant portion of city streets and sidewalks” untouched. Almost a quarter of the total went to one family, members of which collectively owned only 11 registered commercial vehicles—several suitable only for light snow removal—in December 1969. Another sizable payment went to a company owned by a Democratic Party committeeman.

Scott’s first front-page investigative series exposed unsafe and unsanitary conditions at the John Boyd Thacher Homes, a high-rise, low-income public housing project in Albany’s South End. Inspired by tenant activism, the series earned Scott accolades from not only Robert Danzig but also high-ranking members of Governor Rockefeller’s staff, who commended the series for its “bite.” Two months later, in April 1970, Scott scored another front-page scoop—this for a story on exorbitant overtime payments to Albany policemen.

Despite early successes probing corruption in city government, Scott was pulled off the beat. (The scuttlebutt was that Mayor Corning had lobbied for Scott’s reassignment.) But even as he covered suburban tax hikes and teacher strikes, Scott set his sights on a bigger story. On his own time, he began investigating corruption and costly security failures at the massive construction site in Albany’s core.

Like most local residents, Scott had heard stories of rampant crime, corruption, and waste at the South Mall. But the pro-Rockefeller, pro-renewal leadership of Capital Newspapers had, thus far, failed to follow up on these rumors.

In April 1971, Scott brought the results of his independent South Mall investigation to his editors with an ultimatum: Publish my findings or someone else will—and I will publicize your refusal.

As a federal grand jury met to evaluate allegations of gambling and loan-sharking at the South Mall, the Knickerbocker News published the first of Scott’s 6–part, tabloid-style series on April 26, 1971. The young muckraker accused the State of ceding to organized labor responsibility for security. The result was frequent fires, rampant theft, widespread gambling, and labor racketeering, all of which cost taxpayers untold millions. And yet state and local officials failed to act. They treated the problem like a “billion-dollar hot potato,” each denying any knowledge or responsibility.

Although the grand jury failed to bring an indictment that summer, Scott laid out the evidence, including a gambling slip, printed on flash paper so that it could be quickly destroyed should law enforcement appear on the scene. He estimated the annual take by South Mall bookies at $20 million. Since the odds were stacked against gamblers, loan sharks found easy prey. Furthermore, Scott alleged, indebtedness encouraged construction workers if not to steal, at least to look the other way. Theft of equipment and materials—most notoriously, marble slabs—measured in the millions of dollars.

Despite a request from Office of General Services (OGS) Commissioner A. C. O’Hara “not to pursue” the story—on April 30, the Knickerbocker News published an interview with a former employee of the William J. Burns International Detective Agency. “Mall Crime Reports Withheld, Ex-Undercover Agent Says” the headline read. Scott’s informant—whose name was “withheld to protect his safety”—revealed that state officials had hired undercover agents to collect evidence of criminality at the South Mall but that “the evidence has been suppressed, and there have been no arrests.”

Picked up by the UPI wire service, the story of criminal behavior at the South Mall circulated across the state, provoking outrage. Citing Scott’s reporting, two Republican assemblymen introduced a bill to require state troopers to guard the construction site. Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered the OGS Commissioner to conduct an assessment of the security situation, but that report was kept secret, even from legislators. Later in the summer, another federal grand jury was impaneled to investigate the South Mall, and at around the same time, a fire—by Scott’s calculation, the 61st since July 1967—broke out in the construction site.

The Hot Potato series earned Scott second-place in the Hearst National Writing Competition and a personal phone call from William Randolph Hearst, Jr. Hearst was a friend of the governor and editor-in-chief of Hearst Newspapers, which owned the Knickerbocker News. He complimented the young muckraker on his investigative work but encouraged him to take aim at a different target.

That summer, Scott began investigating police corruption. His series on “Heroin & Corruption in Albany” would earn him a Pulitzer Prize nomination and set in motion a 2-year State Commission on Investigation inquiry.

Less than a year later—even while celebrated as a leader of a new tribe of “typewriter guerrillas”—the 24-year-old writer left the Knickerbocker News and began work on a Ph.D. in Criminal Justice. Scott continued to publish articles and books but had become disillusioned by what he regarded as “short-sighted or knee-jerk” exposure. He would later tell author John C. Behrens that he had come to the conclusion that “investigative reporting often results in a situation that is no better, or worse, than that which exists prior to the noble effort.”

Postscript: As a result of Scott’s reporting, our sights are now set on the State’s secret security assessment, the Burns Agency reports, and the FBI’s South Mall investigative files.

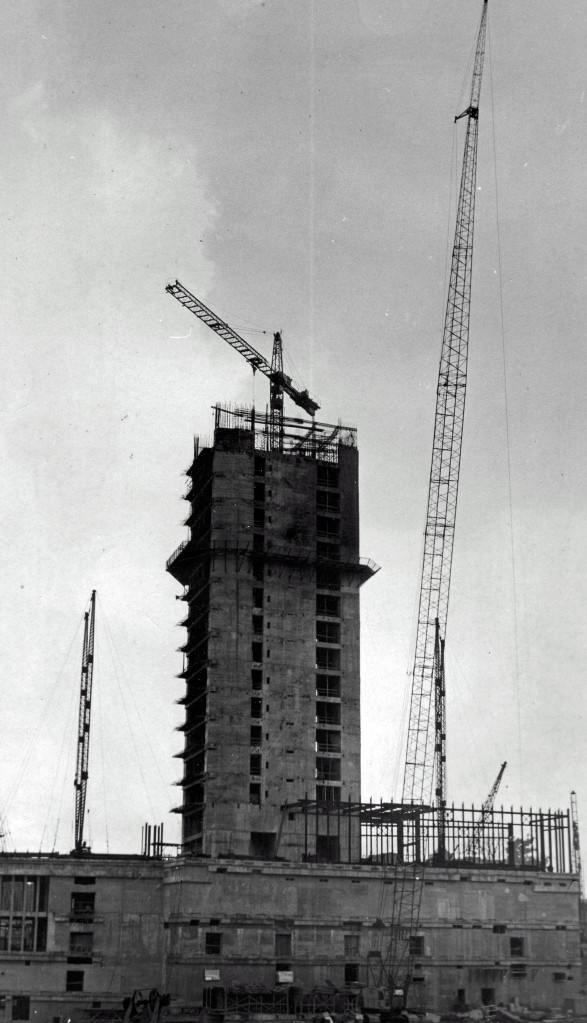

Note: The photograph at the beginning of this post shows the Eagle Avenue entrance to the South Mall construction site, June 1970. Used by permission of the Times Union.

Wow! This is a riveting story! Love the way Scott’s digging and persistence brought this to light. I can only hope that he enjoyed/is enjoying a great career.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, he just published a new book, http://scottchristianson.org/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very Interesting story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. We think so!

LikeLike

Great Post……Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for checking out our blog.

LikeLike

Interesting stuff, keep it up. Can’t wait to read more about this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is great , reminds of a movie I saw where the Chinese just flooded this river and buried everyone’s home , Grewsum and to think these big honchos could go the same thing. done. I hope they paid you a lot. . Sign me up ,or I ‘ll figure it out. thanks b http://artandelephants.wordpress.com

LikeLike

I’m saddened to learn about Christianson’s disillusionment and that he felt such reporting may have made the situation worse. Shall we read between the lines that Hearst encouraged him to take another direction in an effort to dissuade him from pursuing his work on this project?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Scott was encouraged to look for other stories. And he found them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting story. Such dedication Scott had to continue doing investigations on his own. I’m thinking that was a very dangerous undertaking considering the amount of money disappearing in the wrong hands. A brave man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And a very nice man. We enjoyed getting to know him.

LikeLike

I love you, dad. I miss you terribly. I’m SO proud of the person you were!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Emily,

Your father was very kind and helpful to us. We’ll miss his generosity, wit, and insight.

Ann & Dave

LikeLike

I had the privilege to know Scott briefly and am so saddened to learn of his passing. Learning more about him through this writing made me smile so much. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person